EURASIAN CURLEW (Numenius arquata) - Courlis cendré

© Frank Jarvis

Summary

A very large wading bird, with a long down-curved beak, whose identity could only be confused with Whimbrel. It is always very vocal, making a range of songs and calls. Its English name derives from its basic call “cur-lui”

Switzerland is on the very south-west edge of the breeding range of the Curlew, whose core breeding area is to the north-east, although it also breeds in the British Isles and the Atlantic coast of Norway.

In the 1950’s, Curlews bred spasmodically across northern Switzerland. They have undergone a serious populations decline all over Europe since the 1970’s, which seems to have accelerated since the mid-1990’s. Not only have breeding populations declined in number, but a range contraction has also been recorded. In Ireland, the population declined by 78% over 40 years, and in the UK, by 43% between 1995 and 2012 (Balmer et al 2013, Brown etal 2015). Only one breeding site was found in the latest Swiss bird census (Knause et al 2018). Factors causing this include habitat degradation and fragmentation, forestry and agriculture practises, and high predation rates; a recovery plan has been prepared by the RSPB (Brown 2015) as a result of popular concern (www.curlewcall.org).

It is a bird that breeds in wet marshy areas, open, without trees or ravines which could afford cover for predators. It favours wet peaty soils (tourb), especially close to water. These are usually sparsely populated due to the habitat, and so, it is associated with lonely areas that match its mournful cries. It is a migrant across most of its range, moving south when the breeding grounds are usually covered in snow and ice. In Switzerland, it is mostly encountered overwintering or on migration along lake and river margins and, occasionally, in wet fields, mostly in the flatter lands in the north of the country.

Winter flock of Curlews © Arlette Berlie

As a boy, in the north of England, I was taken with my scout troop every March to a moorland area, well away from the industrial town that was my home. I thought this a wonderful place far from cars, trains and factories and I was enraptured by hearing this bird on what were then its breeding grounds. It is a generally noisy bird. Its voice is strident, loud, often seems aggressive, although it is always hauntingly beautiful. As stated, the English name derives from the basic phraseology which is variation on “cur-lui”:

In the sonogram below, you can see the shape of this bold call which announces its presence. It sounds bold because it starts with a sudden rise in frequency as the call almost explodes into the atmosphere. This is particularly clear in the calls at 1.7s, 5s and 5.7s in the video. It then slides slowly up again at first, finally shooting vertically, before finishing with a little trill, about which we will learn more later.

CURLEW STUDIES © Frank Jarvis: centre sketch shows comparison with Whimbrel with dark head-stripe

The “cur-lui” call is delivered both in flight and when stationary and, sometimes, instead of the explosive opening, each phrase is introduced by a drawn-out “croaking” sound:

This “croak” shows in the spectrogramme as a broad range of frequencies:

And when a bird is excited it can be repeated at speed:

Another commonly heard call, more frequently used in flight, also roughly corresponds to the phrase “cur-lui”:

This call has the mournful quality that makes the song of the Curlew so appealing to poets and writers. Perhaps it is the upwards inflection of each phrase and the fact that the last note is lower than the first that creates this effect. The central frequencies involved vary between 1.72-1.8 kHz, roughly from A6 to B-flat6 on a piano (a white key to a black key), so maybe the bird sings in what musicians call a minor key, which always sounds more solemn - but I am not a musician, so this is pure speculation on my part! (Comments from musicians welcome):

When birds are alarmed it all changes. The most common alarm call that I have experienced is a rather soft “whickering” call. This was recorded near the coast from birds on migration:

…and a review of the sonogramme indicates that it is quite different from the previous sounds:

However, this rather “soft” signal of alarm can also changes into something that sounds more aggressive and urgent:

This recording was made on the moorland breeding grounds in the Isle of Skye, Scotland, as the bird flew around me. The sonogram shows yet another shape:

There was perhaps a nest or young nearby, so I decided to leave the bird in peace. But, as I was quietly moving off, one bird came flying in towards me, and took this call to a new level of aggression:

You will notice in these last two calls the up and down wavy lines that show the bird was modulating the sound up and down between two frequencies, giving it a sort of “warbling” effect. This is a technique that the Curlew uses in several contexts (see the first “cur-lui” description in this write-up).

But the most celebrated and beautiful sound is the “bubble” song of the male. It is normally delivered in a song flight where the bird flutters up high, then parachutes down, holding the wings in a shallow “V” over the back, whilst it pours out its song. Upon landing, the wings are again often raised up.

The bubble song normally begins with 2-3 long drawn out notes, then a warbling rolling, mournful wail that rises to a crescendo and falls away again. Listen to this:

Curlew “bubble” song

©Arlette Berlie

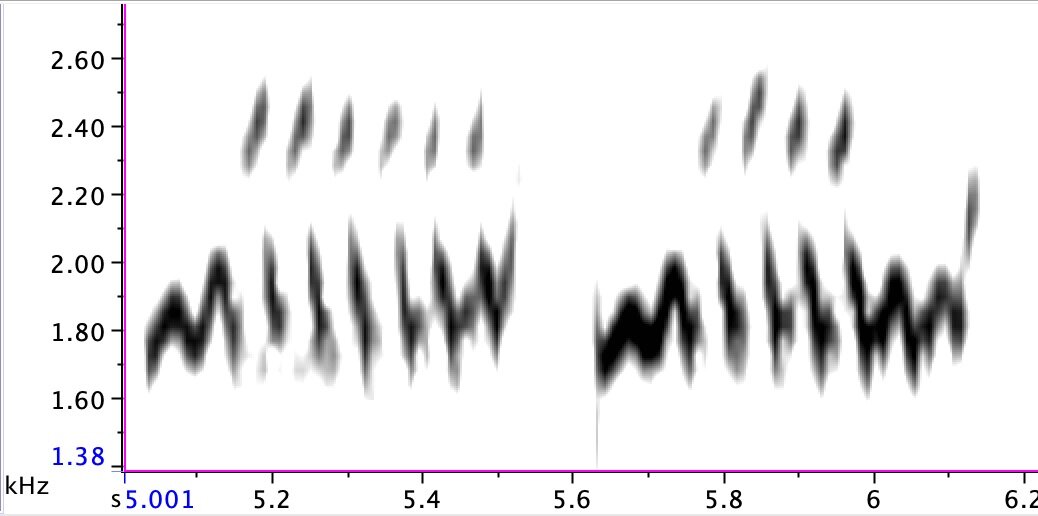

In the sequence shown here, the opening is 3 rising mournful notes, but the number of these can be variable. It then bursts into the “bubble” sequence, rising in pitch and volume before, finally, descending slightly and terminating. This “bubble” name is because it clearly (and justifiably) once reminded someone of bubbles rising in a glass of a fizzy drink. Each “bubble” being represented by a new burst of sound, there are 13 such bursts in the sonogram above. But then, each “bubble” seems to shake around and the burst of sound seems to be modulated up and down very rapidly, visible in what looks like the teeth of a comb in the sonogram.

Detail of two bursts (“bubbles”) of sound from Curlew song

Now, if we look at just two of these “bubbles” and zoom in on them, we can find even more amazing things. First, each burst of sound lasts only about 0.5 sec - very fast! Secondly, there are also about 7 even shorter notes made within the space of this half-second. At first glance, it seems like a note that wavers up and down but, in fact, there are actually two rows of notes, very clearly and distinctly separated on the sonogram. An upper row around 2.40 kHz, and a lower row around 1.9 kHz. And you can see that the upper row is made of notes which start at about 2.3 kHz, rising to 2.5 kHz, and the lower row are notes which start at about 2.1 kHz, falling to about 1.7 kHz. In each row, the notes are separated by only 0.02 sec (that is, two hundredths of a second) and, in that gap, the note on the other row is produced, moving in the opposite direction, almost but not quite simultaneously. So, clearly, something mind-bendingly fast and complex is going on here. How do they do it?!

I have written elsewhere a description of the vocal apparatus of birds and how they have two “voice boxes” (called the syrinx), unlike us, that have only one. Each of these can be worked independently and what I think could be happening when the Curlew sings, is that the bird is juggling the sounds from each side of the syrinx, alternating rapidly from one to the other to create the rapid sounds which occasionally have some overlap. It is quite amazing to do this at such speed, but equally amazing is that the birds to which this is directed have a calibre of hearing that can pick out this detail! Studies of the Cardinal (C.cardinalis) in the USA have shown, in that species, each side of the syrinx is specialised for different frequencies and the bird can switch from one side to the other in what sounds like one continuous note.

If you now go back to the sonogram, you will see that, following the bubble song, the bird emits two mournful cries on a rising note, named the “whaup” call by some authors. This can be used along with other birds on the breeding grounds responding in a similar manner:

Incidentally, this sound called “whaup” is also used as the colloquial name for this bird in northern England and Scotland and, the “whaup” call is often uttered by the male as he ascends in his song flight.

If we now piece all this together, you can begin to understand why these weird and wonderful sounds, when delivered in remote high altitude moorlands, have inspired so many poets and writers to describe them and use them as the backdrop to lonely and tragic feelings and love stories…..and why, as a boy from a noisy industrial town, I fell in love with these sounds in lonely places.

Curlews on Norwegian breeding grounds

Here is a slightly longer piece. Towards the end, you can hear how the song of one male sets off flight songs of others. So, although the moorland is remote and lonely, it all becomes very busy when the Curlews are defending their territories! In this piece, recorded in the Lofoten Islands of Norway in May, you can also hear, in the background, Black Grouse, Willow Grouse, Common Gull, Redshank, Raven and maybe others.