LONG-EARED OWL (Asio otus) Hibou moyen-duc

© Frank Jarvis

Summary

Long-eared Owls are not a rare species, but neither are they common. Their habits and calls are very subtle and discrete, making them hard to see, and their gentle hooting calls are easily overlooked, even though they can carry a surprising distance.

© Lia Maaskant Unsplash

In Switzerland the Long-eared Owl is found mainly below 1100m, it occurs more commonly on the plane but the population density falls off rapidly above 500m. It is not a forest owl, but prefers small groves of trees (preferably with conifers), or forest edge, adjacent to agricultural land. It is a small mammal specialist, preferring mice and voles which it hunts along hedgerows, in rough field edges or fallow land. It seems to prefer proximity to fields growing cereal crops, probably because of the small rodents which also forage there. It is almost exclusively nocturnal, except in mid-summer when feeding young.

They can live in close proximity to humans, but these are very discrete birds and are seldom seen. They have superbly camouflaged plumage, and blend in very easily, especially when sitting close to the bark of a tree a disguise they use as their primary defence mechanism. Even when they form communal roosts, which they do in winter, they are seldom discovered. Another sign of their discretion is their voice which attracts much less attention than, say, the screech of a Barn Owl, or the better known Tawny Owl. The call of the male is a very gentle low frequency hoot:

Despite being such a gentle, subtle, low-pitched hoot, it can carry 1-2 km under calm silent conditions. There is a trick to this that Magnus Robb(2015) points out: it is all to do with choosing a perch at the correct height so that the sound waves reflected off the ground match those delivered directly so there is an additive effect which gives stronger transmission. (The physics behind this is described in Catchpole and Slater 2008 page 89). I also find it very ventriloquial and difficult to locate. The basic note is around 400kHz and each delivery about every 3 s.

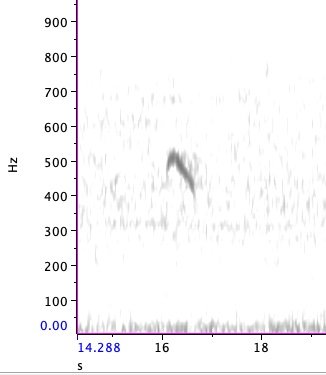

Sonogramme of the male call taken from the sample above.

At the start of the breeding season the male can call most of night in this monotonous manner, the calling being broken up into a series of bouts of up to 15 minutes long. Each bout starts at a lower frequency with the pitch slowly rising, and often the volume too, until a plateau is reached. The video below shows one bird which starts at around 320 Hz until rising to 400Hz after about 20s (with a backing of cow bells from a nearby farm!).

Long-eared Owl male showing rising notes at the start of a calling bout

So that is the male, and all this is about attracting a female at the start of the breeding season. So how does she respond?

I had spent several weeks surveying different patches of trees in a mixed agricultural area by placing a variety of unattended recorders in different patches catching faint recordings of the male call in various places until I finally worked out which was his favourite patch. Since it was the start of the breeding season I did not want to go clambering around at night and disturb them, so I set my kits up in daylight and hoped for the best. My recorders can run for several days until the memory is full.

For many nights I recorded only a lonely male calling all night long from different locations in “his” patch of trees. I wasn’t sure whether there was a beloved out there for him or not, it wasn’t looking tat great. So imagine my joy when suddenly this turned up:

Single call of female Long-eared Owl

The difference between this and the male call is clear: the female calls at a higher frequency ,with the main energy around 500- 700Hz, it is also much more intermittent in calling - not the regular rhythm of the male. The second part of each call involves a downward slide from 500Hz to less than 400Hz which also gives it a certain gentle and rather mournful character. The male on the other hand has a shorter, more blunt, call which terminates abruptly.

This was her first appearance in my recorders and probably right at the start of their (possibly renewed) courtship. Within a few nights she had increased the excitement, and was using her soliciting call (referred to as “nest call” by some authors). This sounds more energetic, has a slightly higher frequency (around 700Hz), but most notably has a slightly rough, or fuzzy edge to it, almost a buzzing call. It is described by some as being like humming into a comb covered by a stiff paper:

Now we were in business, it seemed like a good pair bond was building. There then followed a long period of nights where both called softly back and forth between each other, their higher and lower notes showing distinctly:

(That last piece is edited to reduce the interference from cow bells and a very dynamic frog chorus)

Long-eared Owls do not build their own nests but rather use empty nests of crows, jays, magpies, birds of prey, herons etc. So there is quite a lot of activity around possible nest prior to egg laying. During this period of courtship various display techniques are used. Flying in circles around a prospective nest is one of these, and wing clapping may be used as both a physical and acoustic display (Cramp etal). Wing claps can be done by either sex but more by the male (Voous & Cameron 1988) and the clap is under the body not over (Robb 2015).

Long-eared Owl studies © Frank Jarvis

The following video shows how complex these interactions can get. I think the male is showing the female a nest site, he starts calling and at 19s flying around wing clapping (listen for the sounds getting louder and quieter), at 21s there are soft “clucking” sounds and the male calls fall to a lower pitch. At 38s, as mentioned by Robb (2015) there is a double clap from some distance away (no one seems to know how this is done), and at 47s the female responds with a call followed by several others whilst the male claps away. At 1m18s the male starts clapping very rapidly (with another double at 1.22, and I think the female flies in at 1m23s with a loud thud and calls loudly close to the mics.

Long-eared Owl display flights

Now, the next stage in this audio story of course should be recordings of the young, they have a distinctive high-pitched squeak for a begging call - people compare it to the squeak of a rusty gate hinge. However, not too long after that last sequence was recorded a big storm swept through the area which lasted 24 hours or so - high winds and heavy rain. After it was past I could only hear the male on my recordings, the female returned after about a week, but only stayed two nights or so then disappeared again. Whether she had a “better offer” elsewhere I don’t know. I was hoping maybe she was quiet sitting tight incubating eggs, but although I again monitored at the time the young should have been calling I found nothing, neither adult nor young, and I suspect it was a failed year for them. I need to return next March and see what is going on……